Mi sono trasferita a Milano il 13 gennaio 2020. Ancora non si parlava del virus, eppure in quei giorni il Covid-19 stava già cominciando a diffondersi in Lombardia. Forse aveva viaggiato a bordo di un treno, come me. Forse si era disperso tra gli ampi corridoi della Stazione Centrale, aggrappandosi stretto allo zaino di qualcuno diretto altrove.

Forse, invece, aveva preso un taxi per il centro di Milano e chissà se anche a lui era capitato il tassista che ce l’aveva a morte con Beppe Sala per i lavori della nuova linea della metropolitana, la M4. «Invece di fare tutto questo casino, bastava aggiungere qualche fermata in più alla linea gialla ed era fatta. Tutto questo rumore e poi lo sa quanti soldi pubblici…. Fino al 2021 questo casino eh».

Quello che più ho amato della sistemazione che sono riuscita a trovare, dopo mesi passati a iscrivermi ai siti di affitti più disparati e disperati, è la posizione. Si trova a pochi passi dalle colonne di San Lorenzo, noto come uno dei luoghi più vivaci della movida milanese. Quel posto ha un significato particolare per me. Nell’incrocio tra Corso di Porta Ticinese e via Molino delle Armi c’è Farini, il locale dove feci il mio primo aperitivo milanese quasi due anni fa. Allora non sapevo che un giorno mi sarei trasferita proprio qui e a dir la verità ritenevo Milano piuttosto scialba. Eppure, in quel luogo e in quel preciso momento, mi resi conto di essere felice dopo tanto tempo. Roma, la mia bella Roma, non era stata in grado di mettermi dinanzi a questa consapevolezza.

È un po’ come quando ci si sente più capiti da uno sconosciuto piuttosto che dall’amico di una vita.

Questa zona, oltretutto, mi rievoca uno dei miei film preferiti di Carlo Verdone, Maledetto il giorno che t’ho incontrato (1992). Nel film Margherita Buy abita proprio in un appartamento vicino al colonnato, ripreso in molte scene. Direi che il rapporto nevrotico tra i due protagonisti, Bernardo e Camilla, rispecchia a pieno quello tra me e Milano.

Non la sopporto ma, allo stesso tempo, mi fa divertire come poche altre città.

In alcuni periodi ho bisogno di starle lontana, ma, anche se non voglio ammetterlo, me ne scopro innamorata. Di fronte a Farini c’è la libreria Verso, una delle più attive d’Italia. Organizzano eventi, presentazioni e fanno discreti aperitivi. Il giorno di San Valentino c’era una presentazione a cui avrebbe partecipato Marco Missiroli, anche lui un milanese d’adozione, di cui avevo iniziato a leggere Atti osceni in luogo privato. È un romanzo ambientato in parte a Milano e il fatto che conoscessi quasi tutte le vie indicate mi dava l’impressione di essere parte di questa città. In realtà quella sera alla fine decisi di andare a fare un aperitivo al Tongs, sui Navigli, con i miei amici. Era la prima serata tutti insieme nel ritrovo più alla moda di Milano e sarebbe stata anche la nostra ultima uscita spensierata.

Alla fine tornai a casa prima degli altri perché mi sentivo stanca. Per questo, quella sera si è aggiudicata un posto d’onore nella mia lista dei rammarichi insieme a tutte le cose che non ho fatto, non ho detto, non ho vissuto al massimo prima del virus. Mentre scrivo provo sensazioni strane. Mi sembra di riferirmi alla vita di qualcun altro e di scrivere guardando dall’alto, come un narratore onnisciente.

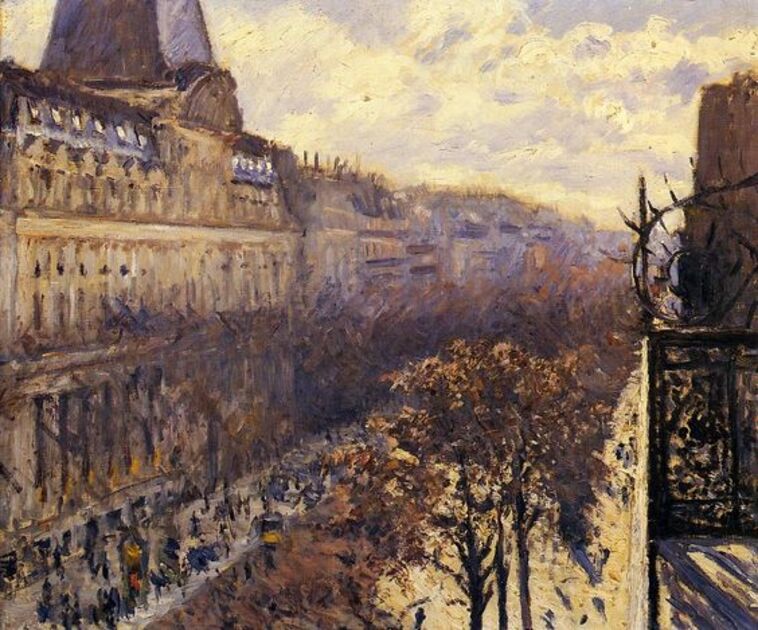

La pandemia che stiamo vivendo ha segnato uno spartiacque tra il prima e il dopo, creando una voragine tra questi due spazi temporali. È difficile parlare di qualcosa ancora in evoluzione ma ci proverò. All’inizio la trasformazione accaduta alla città era la cosa che più mi angosciava. So che non è niente a confronto dell’inferno accaduto negli ospedali e nelle case di molti. Eppure, proprio quel silenzio urlante mi parlava più di qualsiasi bollettino delle 18.

Affacciarmi e vedere le colonne deserte, non sentire le voci, non vedere più le persone indaffarate nella loro quotidianità. Impensabile per qualsiasi città, ma per Milano soprattutto.

Non è necessario vivere qui per sapere cosa Milano sia diventata negli ultimi anni. Se Roma rimane il luogo dell’ispirazione per eccellenza, è Milano il dove da cui tutto ha inizio.

È il motore, la fucina, il laboratorio. La velocità inarrestabile, il senza limiti, il pragmatismo. Non è più una città italiana come le altre, è diventata la città.

Ormai da molti anni assisto all’emigrazione sempre più massiccia di giovani neolaureati a Milano. Per la mia generazione, mai così qualificata eppure penalizzata dalla mancanza di prospettive, questa città è rimasta l’unica alternativa alla difficile decisione di abbandonare l’Italia.

Ripeto: non pensate che il mio rapporto con Milano sia così pacifico. Ho passato momenti in cui non sopportavo più di essere confinata in un posto che in fondo non mi appartiene, in cui ho giurato di non tornarci mai più, arrivando a colpevolizzarlo di essere uno degli epicentri di questa tragedia.

Tuttavia, la parola Milano mi rievoca tante altre cose che non posso dimenticare.

Quella sera di fine gennaio in cui andai alla Feltrinelli di piazza Piemonte per la presentazione del libro di Claudio Martelli su Craxi (qualche giorno dopo avrei visto Hammamet nel cinema di viale Tunisia, in una sala gremita di persone interessate alla storia di uno dei milanesi più famosi della storia italiana). Ero arrivata molto in anticipo per prendere il posto e un uomo elegante sulla settantina, seduto accanto a me, cominciò ad attaccare bottone.

Era simpaticissimo e per questo mi ricordava tanto mio nonno. Passai l’ora di attesa ad ascoltarlo raccontarmi la sua vita. Aveva frequentato lo stesso liceo di Martelli, vissuto la Milano da bere, era diventato un imprenditore affermato, si era innamorato di una donna (romana) quando era già sposato. Nel frattempo, arrivarono anche il sindaco Beppe Sala e Luciano Fontana. Ad un certo punto, l’uomo seduto davanti a me si accasciò a causa di un collasso e fummo noi due, imprevedibili protagonisti del momento, ad intervenire per tirarlo su mentre i relatori guardavano la scena basiti e chiamavano l’ambulanza. Alla fine di tutto, ci scambiammo un “buona fortuna” con quella particolare nostalgia che si prova per tutto ciò che è finito troppo presto.

Quella mattina che ricevetti su Instagram il messaggio da una signora che aveva trovato la mia tessera Atm per strada. La sera prima ero tornata brilla e felice da una serata in enoteca con Miriam, e probabilmente mi era caduta all’uscita della metro. Già mi tormentava il pensiero della lunga fila all’ufficio in piazza Duomo per rifare l’abbonamento, mentre qualcuno girava indisturbato utilizzando la mia carta. Invece, la signora me la fece ritrovare in un bar di Corso Italia all’interno di una busta bianca con scritto “Per Francesca”.

Quella sera che mi feci tre ore di fila fuori dal Piccolo Teatro per assistere allo spettacolo di Daniel Pennac sul suo libro La legge del sognatore ispirato a Federico Fellini. All’inizio eravamo solo una ventina, poi cominciammo ad aumentare a dismisura. Era la prima tappa del tour dello scrittore francese, realizzato per omaggiare il rapporto tra Fellini e i sogni. Era stata scelta proprio Milano per questo debutto importante. Pennac iniziò lo spettacolo, ricreando sulla scena un suo sogno infantile: la lampada del suo comodino comincia a colare. La luce diventa liquido inarrestabile e arriva a riempire tutta la sua stanza, addirittura finisce per inondare la città intera come uno tsunami irradiante.

Se mi chiedete come immagino la fine di tutta questa storia, vi rispondo così: come una luce rigenerante che seppellisce tutto e ci dà la possibilità di ricominciare daccapo. Spesso mi domando se, in questi eventi raccontati, il dannato virus si trovasse lì con me. Sulle mani di qualche signore seduto ad ascoltare Martelli, sulla mia tessera ATM, volando liberamente tra le parole di Pennac. Forse sì. Forse no.

Forse è sempre la stessa storia: in ogni esplosione di vita c’è anche un po’ di morte.

Ancora una volta Milano mi ha fatto capire qualcosa che in realtà sapevo già.

di Francesca Scerrato